Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron

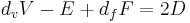

In geometry, a Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron is any of four regular star polyhedra. They may be obtained by stellating the regular convex dodecahedron and icosahedron, and differ from these in having regular pentagrammic faces or vertex figures.

Contents |

Identification

The four Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra are illustrated above. Each is identified by its Schläfli symbol, of the form {p, q}, and by its name. One face of each figure is shown yellow and outlined in red.

Characteristics

Non-convexity

These figures have pentagrams (star pentagons) as faces or vertex figures. The small and great stellated dodecahedron have nonconvex regular pentagram faces. The great dodecahedron and great icosahedron have convex polygonal faces, but pentagrammic vertex figures.

In all cases, two faces can intersect along a line that is not an edge of either face, so that part of each face passes through the interior of the figure. Such lines of intersection are not part of the polyhedral structure and are sometimes called false edges. Likewise where three such lines intersect at a point that is not a corner of any face, these points are false vertices. The images below show golden balls at the true vertices, and silver rods along the true edges.

For example the small stellated dodecahedron has 12 pentagram faces with the central pentagonal part hidden inside the solid. The visible parts of each face comprise five isosceles triangles which touch at five points around the pentagon. We could treat these triangles as 60 separate faces to obtain a new, irregular polyhedron which looks outwardly identical. Each edge would now be divided into three shorter edges (of two different kinds), and the 20 false vertices would become true ones, so that we have a total of 32 vertices (again of two kinds). The hidden inner pentagons are no longer part of the polyhedral surface, and can disappear. Now the Euler relation holds: 60 − 90 + 32 = 2. However this polyhedron is no longer the one described by the Schläfli symbol {5/2, 5}, and so can not be a Kepler–Poinsot solid even though it still looks like one from outside.

Euler characteristic χ

A Kepler–Poinsot polyhedron covers its circumscribed sphere more than once, with the centers of faces acting as winding points in the figures which have pentagrammic faces, and the vertices in the others. Because of this, they are not necessarily topologically equivalent to the sphere as Platonic solids are, and in particular the Euler relation

does not always hold. Schläfli held that all polyhedra must have χ = 2, and he rejected the small stellated dodecahedron and great dodecahedron as proper polyhedra. This view was never widely held.

A modified form of Euler's formula, using polyhedral density (D) and polygon density of the vertex figures ( ) and faces (

) and faces ( ) was given by Arthur Cayley, and holds both for convex polyhedra (where the correction factors are all 1), and the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra:

) was given by Arthur Cayley, and holds both for convex polyhedra (where the correction factors are all 1), and the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra:

Duality

The Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra exist in dual pairs:

- Small stellated dodecahedron and great dodecahedron.

- Great stellated dodecahedron and great icosahedron.

Summary

| Name | Picture | Spherical tiling |

Stellation diagram |

Schläfli {p,q} and Coxeter-Dynkin |

Faces {p} |

Edges | Vertices {q} verf. |

χ | Density | Symmetry | Dual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small stellated dodecahedron |  |

|

|

{5/2,5} |

12 {5/2} |

30 | 12 {5} |

-6 | 3 | Ih | Great dodecahedron |

| Great dodecahedron |  |

|

|

{5,5/2} |

12 {5} |

30 | 12 {5/2} |

-6 | 3 | Ih | Small stellated dodecahedron |

| Great stellated dodecahedron |  |

|

|

{5/2,3} |

12 {5/2} |

30 | 20 {3} |

2 | 7 | Ih | Great icosahedron |

| Great icosahedron |  |

|

|

{3,5/2} |

20 {3} |

30 | 12 {5/2} |

2 | 7 | Ih | Great stellated dodecahedron |

Relationships among the regular polyhedra

| These share the same vertex arrangements: | These share the same vertex and edge arrangements: |

|---|---|

The icosahedron, small stellated dodecahedron, great icosahedron, and great dodecahedron. |

The small stellated dodecahedron and great icosahedron. |

The dodecahedron and great stellated dodecahedron. |

The icosahedron and great dodecahedron. |

The small stellated dodecahedron and great icosahedron share the same vertices and edges. The icosahedron and great dodecahedron also share the same vertices and edges.

The three dodecahedra are all stellations of the regular convex dodecahedron, and the great icosahedron is a stellation of the regular convex icosahedron. The small stellated dodecahedron and the great icosahedron are facettings of the convex dodecahedron, while the two great dodecahedra are facettings of the regular convex icosahedron.

If the intersections are treated as new edges and vertices, the figures obtained will not be regular, but they can still be considered stellations. (See also List of Wenninger polyhedron models)

History

Most, if not all, of the Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra were known of in some form or other before Kepler. A small stellated dodecahedron appears in a marble tarsia (inlay panel) on the floor of St. Mark's Basilica, Venice, Italy. It dates from the 15th century and is sometimes attributed to Paolo Uccello. In his Perspectiva corporum regularium (Perspectives of the regular solids) [1], a book of woodcuts published in the 16th century, Wenzel Jamnitzer depicts the great dodecahedron and the great stellated dodecahedron. It is clear from the general arrangement of the book that he regards only the five Platonic solids as regular, and does not understand the regular nature of his great dodecahedra.

The small and great stellated dodecahedra, sometimes called the Kepler polyhedra, were first recognized as regular by Johannes Kepler in 1619. He obtained them by stellating the regular convex dodecahedron, for the first time treating it as a surface rather than a solid. He noticed that by extending the edges or faces of the convex dodecahedron until they met again, he could obtain star pentagons. Further, he recognized that these star pentagons are also regular. In this way he constructed the two stellated dodecahedra. Each has the central convex region of each face "hidden" within the interior, with only the triangular arms visible. Kepler's final step was to recognize that these polyhedra fit the definition of regularity, even though they were not convex, as the traditional Platonic solids were.

In 1809, Louis Poinsot rediscovered Kepler's figures, by assembling star pentagons around each vertex. He also assembled convex polygons around star vertices to discover two more regular stars, the great icosahedron and great dodecahedron. Some people call these two the Poinsot polyhedra. Poinsot did not know if he had discovered all the regular star polyhedra.

Three years later, Augustin Cauchy proved the list complete by stellating the Platonic solids, and almost half a century after that, in 1858, Bertrand provided a more elegant proof by facetting them.

The following year, Arthur Cayley gave the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra the names by which they are generally known today.

A hundred years later, John Conway developed a systematic terminology for stellations in up to four dimensions. Within this scheme, he suggested slightly modified names for two of the regular star polyhedra:

| Cayley's name | Conway's name |

| small stellated dodecahedron | stellated dodecahedron |

| great dodecahedron | great dodecahedron (unchanged) |

| great stellated dodecahedron | stellated great dodecahedron |

| great icosahedron | great icosahedron (unchanged) |

Conway's names have seen some use but have not been widely adopted.

Regular star polyhedra in art and culture

Regular star polyhedra first appear in Renaissance art. A small stellated dodecahedron is depicted in a marble tarsia on the floor of St. Mark's Basilica, Venice, Italy, dating from ca. 1430 and sometimes attributed to Paulo Ucello. Wenzel Jamnitzer published his book of woodcuts Perspectiva Corporum Regularium in 1568. He depicts the great dodecahedron and the great stellated dodecahedron - this second is slightly distorted, probably through errors in method rather than ignorance of the form. However there is no evidence that these artists understood the regularity of such figures.

In the 20th Century, Artist M. C. Escher's interest in geometric forms often led to works based on or including regular solids; Gravitation is based on a small stellated dodecahedron.

A dissection of the great dodecahedron was used for the 1980s puzzle Alexander's Star.

Norwegian artist Vebjørn Sands sculpture "The Kepler Star" is displayed near Oslo Airport, Gardermoen. The star spans 14 meters, and consists of an icosahedron and a dodecahedron inside a great stellated dodecahedron.

See also

- Regular polytope

- Regular polyhedron

- List of regular polytopes

- Uniform polyhedron

- Polyhedral compound

- Schläfli–Hess polychoron The 10 4-dimensional star polytopes

References

- J. Bertrand, Note sur la théorie des polyèdres réguliers, Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Sciences, 46 (1858), pp. 79–82, 117.

- Augustin Louis Cauchy, Recherches sur les polyèdres. J. de l'École Polytechnique 9, 68-86, 1813.

- Arthur Cayley, On Poinsot's Four New Regular Solids. Philos. Mag. 17, pp. 123–127 and 209, 1859.

- John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, The Symmetry of Things 2008, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 24, Regular Star-polytopes, pp. 404–408)

- Kaleidoscopes: Selected Writings of H.S.M. Coxeter, editied by F. Arthur Sherk, Peter McMullen, Anthony C. Thompson, Asia Ivic Weiss, Wiley-Interscience Publication, 1995, ISBN 978-0-471-01003-6 [2]

- (Paper 1) H.S.M. Coxeter, The Nine Regular Solids [Proc. Can. Math. Congress 1 (1947), 252–264, MR 8, 482]

- (Paper 10) H.S.M. Coxeter, Star Polytopes and the Schlafli Function f(α,β,γ) [Elemente der Mathematik 44 (2) (1989) 25–36]

- P. Cromwell, Polyhedra, Cabridgre University Press, Hbk. 1997, Ppk. 1999.

- Theoni Pappas, (The Kepler–Poinsot Solids) The Joy of Mathematics. San Carlos, CA: Wide World Publ./Tetra, p. 113, 1989.

- Louis Poinsot, Memoire sur les polygones et polyèdres. J. de l'École Polytechnique 9, pp. 16–48, 1810.

- Lakatos, Imre; Proofs and Refutations, Cambridge University Press (1976) - discussion of proof of Euler characteristic

- Wenninger, Magnus (1983). Dual Models. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54325-8., pp. 39–41.

- John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strass, The Symmetries of Things 2008, ISBN 978-1-516881-220-5 (Chapter 26. pp. 404: Regular star-polytopes Dimension 3)

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Kepler–Poinsot solid" from MathWorld.

- Paper models of Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra

- Free paper models (nets) of Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra

- The Uniform Polyhedra

- VRML models of the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra

- Stellation and facetting - a brief history

- Stella: Polyhedron Navigator: Software used to create many of the images on this page.

|

|||||||||||||||||